Wednesday, September 28, 2011

a boy and his father(s)!

Moonshine and Frankenstein

Our own moonlight painting from the Allen: Joseph Wright of Derby's Dovedale by Moonlight:

Monday, September 26, 2011

Properzia Rossi's (and Felicia Hemans') "Fairy world of song and art"

After our visit to the museum last Thursday I began thinking about the inextricable links between poetry and its so called ‘sister arts’, especially in the context of the nineteenth century. Poetry, music and the visual arts were all intertwined as cultured members of society were expected to be well versed in both the Classical and contemporary canons of each. Hemans’ “Properzia Rossi” reflects the connections between all of these arts and explores them through the lens of a Renaissance story of a female sculptor’s unrequited love. After the first two stanzas, nearly every subsequent one makes mention of Rossi’s sculpture (visual art), music, song/sound, and thought, which I take to mean Hermas’ interpretation of Rossi’s thoughts that are then transcribed in the poem. The eighth stanza addresses all of these elements directly, beginning with a reference to the previous stanza: “ Yet the world will see; Little of this, my parting work, in thee” (my italics). “This”, I surmise, refers to Rossi’s “brief aspirings” that “die ere long; In dirge-like echoes,” and “thee” signifies the relief sculpture Rossi creates of her love interest Ariadne. In lines 83 through 85 Hemans states, “Yet how my heart, In its own fairy world of song and art; Once beat for praise!” The stanza ends with: “And tho' the music, whose rich breathings fill; Thine air with soul, be wandering past me still; And tho' the mantle of thy sunlight streams; Unchang'd on forms instinct with poet-dreams” (I believe “thine air” in this instance refers to the blue sky of “glorious Italy” in lines 87 and 88).

The ending line is of particular interest to me in that it is a self-referential acknowledgement of the tangible or intangible “forms” imbued with sunlight and “soul” that inspire the thoughts that become poetry, or “poet-dreams.” Hemans posits this documentation of “poet-dreams” as a as a lasting relic of a bygone era and account of unrequited love that will endure far longer than either its subject or its writer, in the same way that Rossi’s sculpture outlasts both its subject and its maker. This sentiment appears at the very beginning of the poem in lines 9 through 12: “May this last work, this farewell triumph be,–Thou, lov'd so vainly! I would leave enshrined; Something immortal of my heart and mind; That yet may speak to thee when I am gone…” Not only does Rossi’s work outlast its anguished maker, but it is intended to speak, perhaps in poetic verse, to her beloved in her absence, rendering love as “strong as death” (line 59).

Questioning the Spirits in Manfred

Burning in the Fire of Time: Casabianca's Journey to Adulthood

I interpret the flames as the threatening and unstoppable march of time that surrounds and entraps each of us. Time has the power to consume our "ship of life" and even we will eventually perish in this inferno. I am reminded of the recurring theme of time as fire in Delmore Schwartz's poem "Calmly We Walk through This April's Day", the last stanza reading:

Patriarchy

One of the most recurring themes in Felicia Hemans' poetry is nostalgia: particularly a longing to return to the pure, unbroken innocence of youth. Having witnessed her own mother's marriage fall apart, Hemans had a similarly unsuccessful marriage that left her to raise five children in her mother's home. A growing resentment towards patriarchy would result, and manifest itself in several of Hemans’ works. While she would achieve a great deal of success and fame, Hemans' was ultimately unhappy with her life as she grew older, and her poetry reflects this. “Evening Prayer, at a Girls’ School” is a poem that highlights Hemans’ displeasure with men, suggesting that young girls are inevitably doomed to suffer in the name of patriarchy.

In “Casabianca”, however, we see that even young boys are not exempt from suffering at the hands of their fellow men. The poem tells of a young boy-sailor who, along with his father, was killed when their ship was destroyed in battle. Despite his “child-like” form, the boy is a brave “creature of heroic blood”(7), who does his best to imitate his father, the captain of the ship. As the boy repeatedly calls to his father, unaware that he has already perished, there is an explosion that reduces the young boy to “fragments” that are sent flying about the sea (36). The explosion is described as “a burst of thunder” (33), making it seem much more like an act of God than a blast from an opposing captain’s ship. Hemans’ capitalization of “Father” further emphasizes that perhaps the young boy is being forsaken on two levels – by both his own father and God, Father of all. Surely Hemans believed that a boy so young has no place in battle, and equal blame lies on his father, as well as God, for allowing the death of such a “young faithful heart” (40).

A few thoughts on the conclusion of Manfred

After the demons disappear and Manfred begins to die, the meter of the poem becomes more frequently broken with dashes. This occurs particularly with the Abbot’s speech. The breaks in the Abbot’s speech, contrasted with Manfred’s smooth speech patterns with his dying breaths, are unexpected. This dialogue pattern reinforces the message that the living fret more over death than the dying do, consistent with Manfred’s utterance of, “Old man! ‘tis not so difficult to die,” (line 151).

Byron also uses the Abbot as a sort of narrator towards the end of the passage. The Abbot describes Manfred’s physical state—white lips, gasping throat, etc—as he is about to die.

In the last two lines of the poem, the Abbot turns his voice outward and addresses nobody in particular. This is another point at which he serves as a narrator for the story. As a narrator in the last two lines of the passage, the Abbot performs two functions. First, he connects the end of the passage to the beginning, in which Manfred acted as a narrator by describing his surroundings. Second, by replacing Manfred as the narrator, he reinforces the fact that Manfred has died. This adds to the effect of the Abbot repeating the words “he’s gone” / “he is gone” at the beginning and end of the phrase.

The reader could interpret Manfred’s assumption of the role of narrator as a symbol of a seamless integration of life and death. It does seem that Manfred’s body was swallowed by the earth—he felt it heave underneath him (line 148), as in an earthquake. The word “heave” was used five lines earlier to describe the movement of Manfred’s breast, which supports a feeling of Manfred’s body having become one with the earth.

The continuous flow of life into death, demonstrated by Manfred’s easy passing, the Abbot’s assumption of Manfred’s role as narrator, and the imagery of Manfred’s body being swallowed by the earth, ties the passage back to its beginning, which highlighted the takeover of nature after the fall of Rome.

Guilt

The first few lines of the section of Manfred that we were assigned to read, though not spoken by Manfred himself, already set he tone of deep guilt: “If fault there be, I must see him.” Manfred is severely tormented by some guilt. Regardless to his inner turmoil he seems to be outwardly stable and respected by those around him. In fact he seems superior to those around him, he even acts this way towards the spirit. He succeeds in challenging the spirit, which would appear undefeatable and generally represents a successful force in literature, yet Manfred casts the spirit off and decides to take his death into his own hands, “but was my own destroyer and will be my own hereafter.- Back ye baffled fiends! The hand of death is on me- but not yours!” Manfred has made his intensions clear- he refuses to answer to anyone or anything but himself and therefore must be in charge of his own destruction. His suicide will allow him to punish himself and paradoxically it will allow him to escape his mysterious guilt. He no longer must “grovel on earth in indecent decay.” In the beginning of his soliloquy Manfred states: “the night hath been to me a more familiar face than that of man,” admitting his feelings of isolation from humanity and perhaps his familiarity with the thought of death. However, in his last words he forced to overcome his self-imposed isolation from humanity, for he realized the hardship of leaving the “ruinous perfection” when he turns to Abbot and says: “Old man! ‘tis not so difficult to die.” Byron wrote this after his marriage failed due to a scandal surrounding charges of an incestuous affair between Byron and his half-sister, Augusta and their illegitimate daughter, Medora. Because Manfred was written immediately after this and because the main character of Manfred is tortured by an unknown sense of guilt, Manfred could be written out of the shame Byron felt after all his own personal scandals.

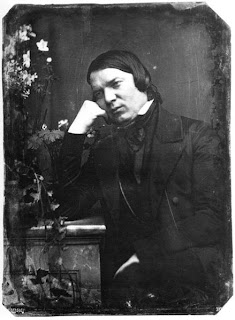

Schumann's Manfred

Schumann is shown here in a daguerrotype from 1852 (source, Wikipedia). The image itself tells a great deal about the importance of the Byronic hero--world-weary (the pose) but beauty-susceptible (the flowers)--on the German composer.

Here is a YouTube performance of Schumann's Manfred Overture, conducted by Wilhelm Fürtwangler. In the mode of 19th-century "program" music, the composer has both tried to create a mood of passion and at the same time has "programmed" in some references to events in Byron's text--the famous scene of Manfred on the heights of the Jüngfrau, and his death.

--NJ

References to nature and the earth in Properzia Rossi

In Properzia Rossi, Hemans, like many Romantic poets, places great stock on nature and uses many comparisons to it. The poem’s protagonist, Properzia, knows her death is imminent. She longs for her soul to be left both as a part of nature (line 14) and in the work that she will leave behind for the man she loved even though her soul could have gained the heights of heaven if she wanted.

Hemens implies that her protagonist’s artistic talents were given to her by God in lines 78 and 79 (I might have kindled, with the fire of heaven, / Things not of such as die!). Later, (line 123) she seems to contend that Earth turns artistic talents into something greater (Earth’s gift is fame.). Properzia feels that this earthly fame is useless if it cannot win the heart of the man she loves. She speaks of her “power” as a “fruitless dower / That could not win me love” (lines 38 and 39). The use of the word “fruitless” seems to make literal sense here- if she had married this man, they probably would have had children. Instead, like a tree that doesn’t bear fruit, she is able to grow faster and stronger and be more independent than a woman with a husband and children. It seems that here Hemens could be hinting that Properzia’s life has been so much more than it would have been if she’d been married.

But later in the poem (lines 95 and 96), Hemens compares watering a flower to giving a woman love and affection, as if this would enable her to grow. Properzia is dying because of a lack of love, just as a flower would die from lack of water. Furthermore, she compares her dreams and passions with fire consuming her (lines 113 and 114 and 134), the opposite of cooling water. It seems like Hemans wants the reader to read into the nature metaphors embedded in this poem and to find both the water of love that Properzia lacks and the fire of passion and of talent that she let consume her.

Nature's Elements in the Eyes of Byron

Sunday, September 25, 2011

There is something almost cinematic in the scale of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. He connects his discontent with the post-Napoleonic War monarchy with a number of past regimes which he deems despotic. There is something slightly contradictory in Byron’s living these fierce anti-governmental protestations through Harold. Not necessarily his complaints about tyranny, but his generalized accusation about nations that are responsible for bringing about the end of despotic institutions. When he says “Fit retribution! Gaul may champ the bit/And foam in fetters;- but is Earth more free?/ Did nations combat to make One submit;/ Or league to teach all kings true sovereignty?” and “Shall we, who struck the Lion down, shall we/ Pay the Wolf homage? proffering lowly gaze/ And servile knees to thrones? No; prove before ye praise!” it is to say that one evil government has been toppled by another that is not necessarily any more just.

In that case, it seems odd that he should have such a reputation for having participated in revolutionary movements. It’s an inevitable pattern- and one that he seems quite aware of- that force is often required to defeat force, and that the defeat of one begets the rise of another.

The Third Canto in particular seems to be a relentless list of seemingly triumphant conflicts which were in actuality bitter evils, or pretty nature settings which have been besmirched by bodies and ichor: “Last noon beheld them full of lusty life,/ Last eve in Beauty’s circle proudly gay,/ The midnight brought the signal-sound of strife,/ The morn the marshaling in arms,- the day/ Battles magnificently-stern array!/ The thunder-clouds close o’er it, which when rent/ The earth is cover’d thick with other clay”.

It is hard to believe that some part of Byron’s imagination wasn’t captured romantically by the scale and grandeur of battle and overthrow, whatever the loss and violence and ultimate consequence. Especially with lines like “While stands the Coliseum, Rome shall stand;/ When falls the Coliseum, Rome shall fall:/ And when Rome falls- the World.” Perhaps revolution was a guilty pleasure for Byron, one he felt the need to check his enthusiasm for with lengthy musings on the pitfalls of such an enthusiasm.

Monday, September 19, 2011

The Dualistic Nature of Light and Knowledge

“Of what a strange nature is knowledge! It clings to the mind, when it has once seized on it, like a lichen on the rock. I wished sometimes to shake off all thought and feeling; but I learned that there was but one means to overcome the sensation of pain, and that was death— a state which I feared yet did not understand.” (XIII, p. 85)

We experience the pained cries of the creature upon his solemn self-realization of the intense isolation that is his existence. After observing the cottagers for weeks and slowly gleaning an understanding of English, the creature finally breaks through after listening to Felix read Ruins of Empires, and at once the light of knowledge seizes him in an implacable bound; while here, we are observing the lichen that is knowledge torment the monster, this could very well have been said by almost any of the main characters. Indeed, Frankenstein and Walton are victims of dangerous knowledge as well, and the theme seems recurrent throughout all of Frankenstein, often manifesting in the metaphor of light as knowledge and science.

Even from the first sentences of the book, it is clear that light is inherently dualistic in nature, representing both exploration and enlightenment, as well as danger and impending doom. We hear Walton lusting for the fruits of the unexplored: “Its productions and features may be without example, as the phenomena of the heavenly bodies undoubtedly are in those undiscovered solitudes. What may not be expected in a country of eternal light. “ But it is this very light that almost sees to his end as he later faces grave danger in the hands of two vast sheets of ice (the light which he wished to explore).

Light, fire, and perhaps more relevantly to the title of this class, electricity, all play incredibly important roles in the life of Frankenstein as well. It is the observation of the devastating, yet awe-inspiring power of lightning that impels Frankenstein into the depths of science and his conquest of knowledge. “…on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak, which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump.” (II p.22) Conversely, it is this very light, the light of knowledge, that will lead Frankenstein into the darkest of depressions, isolating himself from all of his friends and family. And so, it becomes clear that with all light, there is the risk of being burned.

Perhaps the most obvious instance of the dualistic nature of light is portrayed in the creature’s exploration of his new world and his encounter with fire. Prior to the encounter, light is also described with similarly constricting language: “the light became more and more oppressive to me; and the heat wearying me as I walked, I sought a place where I could receive shade.” (XI, p.71) Conversely, the creature also experiences the gentle light of the moon as a sensation of excellent pleasure. Stumbling upon a fire, the creature “was overcome with delight at the warmth…In my joy I thrust my hand into the live embers, but quickly drew it out again with a cry of pain. How strange, I thought, that the same cause should produce such opposite effects!” And so we observe, again, the dualist nature that is knowledge; it provides light and warmth, but also the potential for painful burns.

The idea of light as knowledge seems very well placed in Shelley’s time, as she most likely would have been inspired by Enlightenment thinkers of her time. I’d be curious to know how accurately her perception of science is reflected through the cautionary tale that is Frankenstein: or, the modern Prometheus. (the title itself, a play on the danger that is knowledge).

Images taken from:

http://nuggetsinmuddywater.blogspot.com/2011/08/jim-thomes-600th-homerun.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Koeln_wrm_1044.jpg

vanity

In reading Felicia Heman’s ‘Propezia Rossi,’ the complexity of vanity emerged as a fascinating connection between Heman and Rossi. Aside from the last line, I’d say this is the most defining part of the poem: “From the slow wasting, from the lonely pain, the inward burning of those words- ‘in vain’, seared on the heart- I go.” It is very simple, however, “in vain” in this case (and its repetition through out the poem) doesn’t just mean producing no result. Although the root of the word ‘vain’ is to be devoid of real substance or to be empty, without real substance, through vanity Heman was able to understand and become one with Rossi. Yes, this is in part because of the slow wasting and burning pain they feel but also because of the loneliness of desertion. “Thou, loved so vainly.” The father of Heman’s five children, her husband deserted her and Rossi’s lover deserted her too. After the fulfillment of creating her last work of art, Rossi presented her sculpture to her lover and it was regarded with complete indifference. Understandably such abandonment could only leave one empty, devoid of real substance. Heman writes that it even drains the artistic spirit: “yet all the vision that within me wrought I cannot make thee!” Instead Heman finds other ways to show her vanity, to leave a lingering high opinion of Felicia Heman in the readers mind. Stylistically I think this was done with the repetition “but I go,” “never, oh! Never more” and the abundant usage of long and short hyphens. She is creating a lasting impression, imprinting herself as deeply as possible but also as innocently as possible, almost as if she is lingering in a doorway threatening to leave and victimizing herself. Yet there is no need for her plea: “Of loves kind words to woman! Worthless Fame!” is very human and understandable. In fact ultimately both Heman and Rossi were left with no one to love them other then themselves and therein lies their harmless vanity: “A spell o’er memory, mournfully profound, I leave it, on my country’s air to dwell,- say proudly yet- ‘Twas her’s who lov’d me well.’” Feeling devoid of worth and unable to produce any results having no one to love your empty self but your self will undoubtedly lead to one direction: “Winning but one, one gush of tears, whose flow surely my parted spirit yet might know, if love be strong as death!”

The Homes of England, A patriotic piece?

English 220

Prof. Nick Jones

9/19/2011

Blog Entry 2:

Felicia Hemans “The Homes of England” (858-859)

Felicia Hemans poem “The Homes of England” carries a divided tone. From a less detailed analysis of the poem, the language suggests a patriotic affirmation of the strong English household. This mention of the English household includes numerous references to the church, a powerful institution of the state. When taking Hemans history of being abandoned by the male figures in her life into account, (most notably her husband, Captain Alfred Hemans) the lack of any strong male presence in this poem suggests an undertone of pessimism in regards to the integrity of male support as a crucial piece of the English household.

“The stately Homes of England,/ How beautiful they stand!/ Amidst their tall ancestral trees,” Hemans opens her poem by framing the English household. Her mention of “tall ancestral trees” is a reference to a legacy of strong English households, perhaps a suggestion that this has been the backbone of England’s success through the recent and more distant decades. “There (the homes of England) woman’s voice flows forth in song,” Hemans mentions the voice of the female in the household, this links her gender with the success of the English household, something fundamental to the success of England. “Solemn, yet sweet, the church-bell’s chime/ Floats through their woods at morn,” The author mentions the institution of the church as an element of the strong English household. By mentioning the church, Hemans enhances the poem to that which is beyond merely gender and the household. The English household becomes a symbol for the country itself, with the church as an integral part of a powerful legacy.

The mentioning of the church dilutes the work as a visible critique of the masculine gender. Yet the author’s omission of any reference of the masculine serves to add an undertone that questions the validity of the male as an integral piece of England’s powerful legacy.

Progressive Language and Conservative Ideologies

While reading Hemans’ work I found myself unable to extricate it from the work of both Percy and Mary Shelley. The works of both Shelley’s expressed at times tumult, passion, mysticism and despair, and were engaged with existential concerns throughout. Percy was a bohemian rebel, challenging contemporary social and moral standards and was exiled as a result. Mary subverted such conventions by writing from a male point of view and addressing serious socio-psychological issues in Frankenstein. Hemans, however, seems to reproduce contemporary mores and perpetuate female ideals of delicacy, purity, and faith through both her subject matter and style. Looking at The Homes of England specifically, Hemans paints a poetic picture that is deeply rooted in domestic, nationalistic, and religious ideology utilizing a relatively simplistic rhyme scheme and singsong rhythm. While Hemans does focus on a casualty of the Napoleonic Wars in “Casabianca”, albeit a “young and faithful” child, in “The Homes of England” Hemans addresses the home front. She extols the praises of the “stately…merry…blessed…free” and “fair” homes of England seemingly as a battle cry for those on the front lines to defend the values of their homeland and those, ostensibly women, at home to defend these values accordingly by ensuring that their “…child’s glad spirit loves; Its country and its God.”

Perhaps I am reading this poem from a distinctly 2011 perspective, but I was struck by the differences in tone and subject matter between the work of the Shelleys and Hemans. Not to say that one must be a political or social radical to be a literary Romantic, a style to which Hemans’ vivid and expressive language clearly adheres, or that a poet must be a rebel or revolutionary to be taken seriously. In sum, what most interested me about Hermans’ work was her utilization of theatrical, Romantic language to express socially conservative ideals.

Casabianca - an allegory?

However, while poking around on the internet for further information on the poem and the story of Casabianca, I read somewhere that Elizabeth Bishop, a modern American poet, wrote her own version of Casabianca, indicating that Hemans intended this poem as an allegory for love. Once I read this, and reread the poem keeping Bishop's version in mind (you can see it below), I saw the poem in a completely different light. While we can't be completely sure that this is an allegory that Hemans intended, the repetitiveness of the boy begging his father to respond to him, and the ballad sing-song-y nature of the poem, often reserved for epic love ballads (such as The Highwayman by Alfred Noyes, a poem I had to memorize countless times throughout elementary school), make this interpretation quite plausible. It also definitely gives this seemingly very straight-forward poem another, more interesting dimension. I feel like the final lines of the poem, emphasizing the boy's "young faithful heart" could also support this interpretation, as well as the fact that love and faithfulness are definitely themes that reoccur in Hemans' poetry.

I'll leave you to draw your own conclusions, but as promised, here's the Elizabeth Bishop version for comparison:

Love's the boy stood on the burning deck

trying to recite 'The boy stood on

the burning deck.' Love's the son

stood stammering elocution

while the poor ship in flames went down.

Love's the obstinate boy, the ship,

even the swimming sailors, who

would like a schoolroom platform, too,

or an excuse to stay

on deck. And love's the burning boy.

Casabianca and the Glorification of Circumstance

As exemplified by the the title given to this era of literature, one of the chief uses of poetry and prose is to romanticize situations. The scenario in Casabianca is already very dramatic, so past an elegant description, it seems like Hemans’ work is already mostly done for her. But there are definitely still assumptions to be made, characters to devise, intentions to project and virtues to attach.

Lines like “Beautiful and bright he stood/ As born to rule the storm” associate the child with powers and a presence that in reality may have been replaced by a simple, wide-eyed fear. Of course, Hemans makes it clear that the boy is in fact terrified, and wants to leave. “‘Speak, Father!’ once again he cried,/ ‘If I may yet be gone!’” is just one of his frightened requests. Yet, in spite of this very reasonable fear, and his ignorance of his father’s incapacity, she makes a presumption of the boy’s strength and fortitude, as though he is in complete control of his decision- he is “proud,” a “creature of heroic blood”. The storm, in fact, has all the power here, and the child’s eagerness to leave, while understandable, is an unusual qualification to encounter in an encomium of this kind, and is a reminder of a reality that the poem otherwise gentrifies.

Poets aren’t alone in this trend of honoring victims of circumstance with conjectural commendation. Historical figures who are regarded as heroes are frequently tied (almost automatically) to righteousness and courage if they have taken part in any kind of significant peril. The boy’s presence on the ship during an event beyond his control has made him a hero - that and his instinctual disinclination to leave his father, who he thought to still be capable of hearing him. On the evidence of having seen the child floating on a plank with his father in the aftermath, we are (as the poem would seem to have it) to ignore the possibility that given the clear choice between death and an unconscious father, the boy may well have jumped, had the opportunity not disappeared before he knew it.

The last line “But the noblest thing which perished there/ Was that young faithful heart” seems particularly unfair, given that the others aboard the vessel may well have waited on comrades and happened to make it off in time. This kind of romanticism seems almost disingenuous to any people who had been tied to the event, which at the time was still relatively recent. But in the long-term, the populace seems to have taken it in stride, as the poem is well-remembered and, it seems, well-loved. People (myself included) are reluctant to begrudge a child the possibility that he made an unambiguous choice of death over abandonment of his father. This kind of second-guessing in strong tributes can make for some resentful people in some cases, namely those who knew the gritty truths about the celebrated figure in question.

But in this instance, the nameless boy is the vessel through which a grand story is told, not a politician with as may detractors as admirers. And in the world of Hemans’ poem, if not in reality, the child is noble, and doughty. This poem is representative of that function of literary artists to reinvent and reinterpret events on a scale of their own imaginings. A powerful enough piece of this nature can come to define the real event in the minds of many of the readers- especially those without a contextual introduction on the preceding page. And that’s why it’s a potentially dangerous use of romantic narrative. But here, I think it’s applied very nicely. The image is so dramatic, and evocatively depicted, that art is made from what is ultimately unlucky circumstance, and not an uncommon one at that.

No Rhyme or Reason

Perhaps because it does not strive to rhyme, the opening lines are my favorite part of the poem. While rhyming can certainly be a poetic strength, adding force and memorability as well as aesthetic beauty, it often seems to me that forced rhyming is the most common shortfall of the Romantic poets--perhaps because they felt they had no choice but to rhyme, they occasionally shoehorned words into somewhat awkward rhymes. It is refreshing, then, to see Hemans write a passage in which she pays seemingly no attention to end rhymes.

The difference in rhyme scheme from the rest of the poem (which is divided into sections and mostly rhymed in couplets, with a few exceptions) also serves to set the beginning apart as a sort of prologue. This is emphasized by the numbering scheme, which begins with numeral 1 at the second section. One final notable aspect of the rhyme scheme is that many of the sections end with "orphan" unrhymed lines, as with "If love be strong as death!" in line 58 following the "flow/know" rhymes of line 56-7. At the end, however, Hemans uses a couplet to conclude the poem; this shift lends the final lines an extra degree of finality.

Frankenstein: Questioning Humanity

Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus

Mirroring in Frankenstein

The Hypocrisy of Romanticism?

|

| Felicia Hemans: The Lone Lady in a Man's World? |

Sublime, Frankenstein, and Chinese Evil Spirit

In Frankenstein discussion, I found more in "Sublime". I realized that the sublime mode is not just about grand stories/pictures of beauty, terror and thick colors. It is more about the big emotions that are expressed in the stories/pictures and the big emotions the stories/pictures evoke in us.

When we talked about "Sublime" in class, the image of Xiaowei, a fox spirit from a Chinese movie named Painted Skin, appeared in my mind. In the movie, Xiaowei's face always looks pale and blank. She is looking at somewhere, but she seems to see nothing. She is there. We can see her. But she is absent from where she is. And her voice sounds like it comes from nowhere. Her look and voice don't have any thickness in colors, but the terror she brings is overwhelming. So I think this is also sublime. You can see the look I described in the following pictures of Xiaowei.

_________________________________________________

You can find more information about the movie on wikipedia.

Here is link a song named "Painted Heart" from Painted Skin. In the video you can see the clips from the movie. I like how the beauty of the music works with terror and darkness in the movie.

And you can see another clip here. In this clip, Peirong, the kind-hearted wife of the man Xiaowei loves, comes into Xiaowei's room to tell her something. Then, Xiaowei takes off her human skin all of a sudden. Paiting her skin, she tells Peirong calmly, "Go and tell everyone who I am. However, anyone who knows my secret is doomed to death." Just as Xiaowei's evil nature takes off the human skin and destroys Xiaowei's beautiful human image, in Fankenstein, the creature's first horrible appearance shatters Frankenstein's dream of creating the perfect human being.