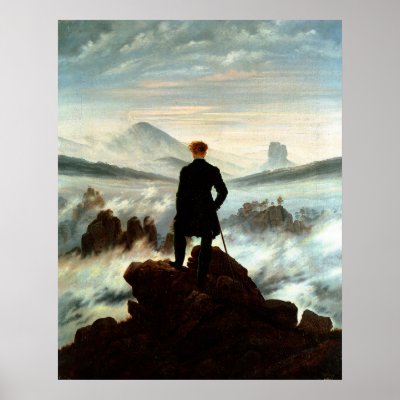

As I was looking at Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog in one of the earlier posts on this blog, the sort of romantic wandering depicted in the painting really reminded me of some of the poetry we had read by Wordsworth. To me, the vastness of the landscape that Friedrich depicts, very mysterious and unknown, and the wanderer's relationship to this nature is reminiscent of the kind of nurturing, almost religious relationship that Wordsworth talks about in his Prelude. Friedrich himself was a deeply religious man as well as a Romantic, and so in his paintings he often references the glory of God through his depiction of landscapes—which I think is definitely apparent in the mystery and vastness of the world that he presents in this painting. The idea of the wanderer is also something that Wordsworth touches on in “Tintern Abbey”, which has that sort of “in between” and wandering feel in both the speaker’s state of mind as well as in the language. And yet, this wandering leads the speaker to important insights about nature, life and memory, which could be reflected in the Friedrich painting: while we cannot see the wanderer’s face, his head appears to be downturned as he surveys the landscape, standing on the precipice of the cliff, most likely contemplating the beauty and magnificence the scene before him and noting his own smallness in the face of it all. This idea of the wanderer, as displayed by Friedrich and Wordsworth, is something that would be carried throughout Victorian art and culture for the next century, with works such as William Morris’s Earthly Paradise, in which a group of wanderers who have been expelled from their war-torn city act as the main speakers, touching on this feeling of “in between” that permeated British society at this time.

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Wandering in Romantic Literature and Painting

Friday, December 16, 2011

The origins of "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison"

It seems then, in this light, like Coleridge was feeling similarly loving and (perhaps this is a bit too strong of a word, but) resentful towards both his wife and the lime-tree. Regardless of whether or not he actually felt resentment towards his wife regarding the miscarriage, both the lime-tree and his wife were living things he loved and found beautiful- but also imprisoned him. Interestingly enough, while this poem was meant to be dedicated to the general group of friends with whom he had been spending time that summer, including his wife, her name was left out of the dedication upon publication. It is certainly a stretch to say that the poem represents disdain or resentment that Coleridge might have felt towards his wife. However, I think its fascinating to do a little detective work and figure out the state of mind that an artist is in when he creates his art; to broaden perspective while reading poetry.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

To Autumn, a painting

I do not understand quite how the poem "To Autumn" and this painting based off of the poem are related. I see no images from the poem, which I understand may be too literal of an interpretation for the artist. However, I also do not see any of the sentiments in the poem. I see only a nice painting of some trees by a lake with a pretty background. I don't see the growth or the sweetness from the first stanza. I suppose I can see a little bit of the calmness and waiting patiently of the second stanza, but that is not what the poem's focus is. I don't see the maturity in the last stanza. And, furthermore, I don't see the cyclical nature of the poem, which I suppose may be hard to paint. Nonetheless, this painting is not what I expected when searching for a painting based on this poem. I feel like it doesn't encapsulate anything the poem is trying to convey, nor does it propose similar sentiments.

I do not understand quite how the poem "To Autumn" and this painting based off of the poem are related. I see no images from the poem, which I understand may be too literal of an interpretation for the artist. However, I also do not see any of the sentiments in the poem. I see only a nice painting of some trees by a lake with a pretty background. I don't see the growth or the sweetness from the first stanza. I suppose I can see a little bit of the calmness and waiting patiently of the second stanza, but that is not what the poem's focus is. I don't see the maturity in the last stanza. And, furthermore, I don't see the cyclical nature of the poem, which I suppose may be hard to paint. Nonetheless, this painting is not what I expected when searching for a painting based on this poem. I feel like it doesn't encapsulate anything the poem is trying to convey, nor does it propose similar sentiments. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog - Friedrich

I think this painting is one of the best embodiments of the Romantic period there is. It is "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" by Friedrich. It's depiction of a man standing awestruck and pensive, staring at the natural scene in front of him is symbolic of the whole movement. During this time period nature was deemed a type of omnipotent, uncontrollable might to whose might we must acquiesce. He seems to be in love with the beauty of the scene as he stands high atop a peak and look out and down at the world. However, there is still a sense of power and majesty that the world has that he both revere and fear.

I think this painting is one of the best embodiments of the Romantic period there is. It is "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" by Friedrich. It's depiction of a man standing awestruck and pensive, staring at the natural scene in front of him is symbolic of the whole movement. During this time period nature was deemed a type of omnipotent, uncontrollable might to whose might we must acquiesce. He seems to be in love with the beauty of the scene as he stands high atop a peak and look out and down at the world. However, there is still a sense of power and majesty that the world has that he both revere and fear. Kubla Khan

The Prelude and Nature as Continuity

It seems quite fitting that we conclude this semester with Wordsworth’s The Prelude, a piece that Wordsworth worked and reworked for the last forty-five years of his life and yet never completed (although of course it is by no means fragmented in its posthumous publication). Written in response from the urge of Coleridge, the poem explores so much of what this course has grappled with: what does it mean to be a poet? How do poet’s see and interact with the world in different ways than us? And what is the role of nature to the poet?

In engaging these broader questions I was struck most significantly by the eleventh book of The Prelude, in which the subject of nature and childhood are explored as the way in which we connect to our pasts. For Wordsworth, there exist certain “spots of time” in a poet’s life that stand out as “renovating Virtue”. It is in these moments, the moments that are often inextricably tied to nature that the poet is born. It is these memories that the poet’s personality and perspective is formed. So it is nature itself that constructs who we are. Nature is the continuity between what we are now, and what we once were as a “thoughtless youth”. This notion of nature as the continuity of our lives seems central to romanticism at large, and it makes sense that we would end on such a powerful and consolidating note. At the same time, I wonder what it would’ve been like to start with Wordsworth, and to have framed the entire course through the continuity of nature; I actually don’t know how different it would be, since we see nature as a means of communication with the past and present in so many of the romantic writers we encountered.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

We are seven

Ode to a Nightingale

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Wordsworth's Tintern Abbey and "Spots of Time" from The Prelude

Soot to soot

The strangeness of the first setting calls to question the "inaudible" quality of dreams that he speaks of: are dreams inaudible because they remain out touch and we are often unable to grasp them when we wake? The structure of the motif of dreams in the poem is surely consistent with the weaving of its overall structure in that its scale and characteristics morph throughout its verses. His dreams are at once both sleeping and waking with "unclosed eyes," and it is often unclear when he is supposed to be dreaming or whether its a dream within a day-dream. Coleridge seeks to ground us back in his cottage at midnight with the cyclical mention of frost.

Monday, December 5, 2011

Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”: a Moral Tale with Supernatural Elements

English Blog entry 6

Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”: a Moral

Tale with Supernatural Elements

Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient

Mariner” is interesting in that it combines a message of morality, similar to

the hubris and folly that afflicted heroes of the classical Greek plays and Homeric-era

epics, while also carrying elements of the sublime and spirituality within

nature that are typical of the romantic era in which it was written. The Mariner

foolishly kills an Albatross early on in the poem. His penance is extensive and

grim; including the death of his crew, and the destruction of his ship. He is

left with a future in which he must travel the vast lands of the earth,

spreading a message of “love and reverence” to all things “God made and loveth.”

Amidst

this story of the Mariner’s poor decision and subsequent curse, is a variety of

spiritual elements that exist in the seemingly magical world of the ocean. In

the fifth stanza on page 574, the Mariner describes the beauty of water-snakes swimming

under the moonlight. The snake is often a symbol of Lucifer, yet in this

context it is enchanting to the eyes of the Mariner. This spiritual beauty transcends

to the level of the sublime when the corpses of the Mariner rise up from the

dead, guided by angelic spirits to sail the ship. While this scene is

beautiful, the notion of a corpse rising from the dead has an element of impossibility

that evokes the horror of the sublime. The atmosphere in which the corpses rise

up is one in which the natural is emphasized; “Beneath the lightning and the

Moon/ The dead men gave a groan (329-330)”. The supernatural of this scene

draws power from the natural world of the ocean, a place in which the

impossible can be possible.

Ultimately Coleridge fuses a narrative

of moral folly with elements of the sublime and supernatural, creating a work

wholly unique in its fusion of traditional and contemporary (romantic) methods

of writing.

Why a Wedding?

The Romantic Artists' Depiction of Manfred

Kubla Khan, or is it?

The Riches of the Forgotten

Upon reading Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, I was immediately struck by Coleridge’s expansive imagination and the poem’s peculiar context and framing. The preface was extremely confusing to me at first since I was not sure who was actually speaking, but after it became clear that Coleridge was reflecting on his own experience, I was still a bit confused as to why he framed the poem as an exploration of “psychological curiosity” rather than on the “grounds of any supposed poetic merit”. I suppose this was somewhat resolved when I understood that Coleridge felt that this was only a “fragment” of the whole piece that he wanted to write, but prefacing it that way still seemed oddly defensive. Then again, it seems many of the romantics were facing extremely harsh criticism, so it seems natural to assume that stance.

After making it into the beginning of the poem, the divide in Coleridge’s language in the eight to ten scattered lines “of exception” and the rest of his attempt to recollect his transporting dream was stark. Most obvious at first was the difference in rhyme scheme, but perhaps even more pronounced than the shift in rhyme was the shift in tone; the first stanza seems to flow quite naturally, and while the second is in no way bulky or unwieldy, it felt a bit more calculated. As Coleridge contrasts the confining walls of the pleasure-dome with the measureless caverns through which the river flows it immediately feels as if the poem is trying to work on me. This impressing tone continues throughout the rest of the poem, by no fault, though noticeably different from the loose, flowing, dream-like, language of the first stanza. This not-so-subtle shift made me think about the conception of this poem and if the story really is true, what this poem would have been if Coleridge was not interrupted by the man form Porlock – honestly I’m not sure if it would have been nearly as engaging. To me the most interesting parts of this poem seem to stem from what Coleridge cannot remember, and the way that he fabricates his dream as a medium for poetic expression.

The Romantic imagination in Tintern Abbey

"...Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world

Is lighten'd:--that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame,

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended , we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things." (lines 36-5o, "Tintern Abbey")

For me, this was the section of Tintern Abbey that best exemplified the Romantic imagination. It is the moment in which Wordsworth turns from what he can see to what he can see within--to his thoughts and ideas. This passage begins with heavy language, as he speaks of the "burthen of mystery" and "the heavy and the weary weight of all this unintelligible world", but it makes a dramatic shift as the burden "is lighten'd", and he transitions into his description of what he considers to be the Romantic imagination. He creates Romantic imagination as an inward reflection, completely serene and lacking the sublime elements we see in something like Fuseli's The Nightmare. It is a state of being that is removed from the body, as one becomes "a living soul" as "Even the motion of... human blood [is] suspended." He posits it as almost indescribable, using smooth and serene language without visual imagery as Coleridge does in Kubla Khan--instead the Romantic imagination is characterised by pure feeling and understanding, or more specifically, feeling and understanding the most essential and simple elements of life, as "the power of harmony... and joy" allow us in this state to "see into the life of things." Overall, Wordsworth's version of the Romantic imagination presents a sharp contrast to other versions of the idea that we have looked at in class, as well as paves the way for the authors' further reflections in the poem.

Layers of Fiction in Kubla Khan

I tend to think this because after reading about "Purchas's Pilgrimage" and its absolutely immense volume, I doubt that it would be a book that Coleridge would happen to be carrying around with him. Like I stated previously, I also find it strange that he would be writing in the third person, and perhaps switching to that register is a way of letting us know that he is not the narrator of the poem. I also read an interesting interpretation of this poem that claims that the interruption of the person from Portslock could have been written as a means of shortening it and therefore being able to properly call it a "fragment". There is often (if not always) more than meets the eye or ear as far as Romantic poets are concerned, which makes it the most fun to pick apart and put back together like a gorgeous puzzle. Even if I'm adding my own layer of fiction here, and if our own analyses don't reflect the author's intentions, isn't the actual leaving of the art to the people of the earth the real intention of the artist anyways? Maybe not the case for all artists, but definitely for those of the Romantic Age.

I would also like to point everyone in the direction of this wonderful article concerning Coleridge and science by Radiolab's Jonah Lehrer: http://scienceblogs.com/cortex/2009/07/coleridge_and_science.php Go read it! It rocks

Coleridge in Darkness and Silence.

In "Frost at Midnight" Coleridge contrasts the loud world outside his cottage with the peace and silence that he finds within. He at first believes this to be a separation of himself and his child from the world, but as he pays closer attention, there is sound even within this cottage. The soot in the hearth grate, though a small sound, "By its own moods interprets, everywhere/echo or mirror seeking of itself,/and makes a toy of Thoughts"

In remembering his school days, he reflects on how, although he was isolated, his child will be free to roam and experience the world without restriction. This child will prosper under the noise of the summer birds or the silence of the winter frost.

These familiar contrasts allow the reader to involve multiple senses when reading these poems. The imagined visuals of sunlight streaming through a canopy of leaves, or the well-known feeling of an uncomfortably quiet room, suggest realistic settings. This is unlike some poems like "Ode to the West Wind" or "O Solitude" that give only a little thought to the setting in which the poem takes place. For Coleridge, the setting is very important, both to ground the reader, and to serve as a character of sorts - one whose emotion interacts with the narrator in a meaningful way.

Kubla Khan, Modern Version

The version I post here (as with all things) cannot match the memory-magnified purity of that first moment, but I'd like to share it anyways. Also, if anyone is interested in folk music I wholeheartedly recommend David Olney, he is a fantastic musician and songwriter (he also has renditions of other classic poems on his Youtube account, though I can't vouch for their quality). Also, I don't seem to be able to create a hyper link using this blogs tools for some reason, and it won't show up, I will instead just post the address where the video can be found.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AK5EcMxuQzk

Nature and Youth in Coleridge

“Frost at Midnight” is, in many ways, a personal interpretation of the guiding principles of early Romanticism. Nature is idealized, given power and agency while being directly linked to personal imagination. Yet the alienation of Coleridge’s childhood distances the poem from the unbridled joy of, say, Wordsworth.

Wordsworth was born and raised in the countryside, a background that permeates all of his work. He depicts childhood as a time when connection to the world around him was at its most intimate. In “Tintern Abbey,” he mourns the loss of the “appetite: a feeling and a love” with nature as he grows older. The natural world granted him serenity and stimulated his imagination, an organic and pure happiness that is seldom seen in Coleridge’s works.

The speaker in “Frost at Midnight,” in contrast to Wordsworth’s rural upbringing, grew up “pent in cloisters dim,” able to seek refuge only in the “sky and stars.” There is no refuge in the memories of his past, no profound emotional imprints for him to call upon. The deep isolation of his early years is reflected as he addresses his child. He promises that his son will “wander like a breeze,” guaranteeing a freedom both spiritual and physical that he himself never experienced. He leaves the night he is currently surrounded by for the “leaf and stem…dappling its sunshine” and a tree with a “deep radiance,” underscoring the illumination achieved through contact with nature.

Where as Wordsworth’s youth was a sanctuary for his “fretful” adult life, Coleridge speaks of this emotional connection with wonder. He treats it as a fragile and unstable connection, one that Wordsworth speaks of as inevitable. “Nature ne’er deserts the wise and pure,” he says towards the end, an almost mournful recognition of a bond he was deprived of.

Monday, November 28, 2011

Mankind's Saving Grace or Family Romance

Wordsworth associates a youthful perspective on nature with anguish in desire, anxiety, and unconsummated love, whereas his view of a matured and more resolved bond with nature is one of peace; a quiet and enlightened recognition. It means an appreciation for the small moments in life and simple pleasures of living, such as "life and food" and at that "for future years" to come. He claims that there is comfort in the continuum of life--in the fact that even after we "are laid to sleep," another generation will sprout up and continue to feel and enjoy the impression of nature upon them.

Form & Content in "We Are Seven"

"But they are dead; those two are dead!

Their spirits are in heaven!"

'Twas throwing words away; for still

The little maid would have her will,

And said, "Nay, we are seven!"

The fairly simple language and rhyme scheme are so musical and easy to read in order to show that, much like the little maiden shows the pompous-seeming narrator (who remains unmoved by her wonderful way of treating death and insists that his trying to talk sense into her is wasted), the most fruitful, beautiful and deeply meaningful messages don’t always come in beautiful epic stanzas with gorgeous metaphors, etc. We can find so much beauty and truth in simplicity as opposed to many people’s incessant need to forever make things more complicated to find beauty in them, as well as the beauty and truth in just accepting the way the world functions instead of incessantly questioning its ways.

"Of eye, and ear,-both what they half create, And what perceive;”

The fact that Tintern Abbey provides a backdrop for Wordsworth’s poem is relevant in ways both literal and symbolic. Composing this work after a visit to the Gothic abbey afforded Wordsworth the ideal setting for a rumination on nature, the passage of time and the gains and losses of memory. The fact that the Abbey does not appear in the poem renders it more of a symbolic destination for Wordsworth, eschewing the splendor of the actual ruins for a sublime psycho-visual creation of mind and memory, as

“a lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth; of all the mighty world

Of eye, and ear,--both what they half create,

And what perceive;” (103-107)

An abbey is traditionally a place of contemplation, spirituality, and transcendence. Wordsworth moves away from Tintern Abbey towards unbounded nature, perhaps as a metaphor for moving away from religion as the means to attain transcendence and finding spirituality in nature. The absence of the actual Abbey in the poem and its emphasis on nature also points to this move towards nature as the conduit to transcendence. If nature and sensory perception are such conduits, the space of contemplation would then become the mind as opposed to an external site. As Wordsworth stated in the quote Professor Jones provided from the Preface to Lyrical Ballads, poetry stems from an emotion evoked through tranquility (nature) which is then contemplated until “the tranquillity [the extrinsic/sensual experience] gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.”

Thus, the mind becomes a space for both contemplation and creation, and the senses serve as both perceptive and creative forces in that they take in “all that we behold” and interpret such impressions that become catalysts for reflection and artistic creation. This idea of sensory/physiological perception as opposed to cognitive/conceptual perception to me relates to the notion of the picturesque landscape. The artist sees an actual landscape, reflects on it, and then interprets it in a way that transcends reality. Thus what is presented as a landscape is a fusion of both what the “eye and ear…half create, and what [we] perceive”.